Text Written by Sylvie Hawkes

It’s 6:30am on August 23rd. I wake up in my cabin at the Sayward Valley Inn. We’ll be spending the next two weeks in the village, around 40km North of Campbell River on Vancouver Island. It’s a 10-minute drive to our restoration site. I see elk foraging in the fields along the drive and then wait for the light to turn at the one-way bridge on Sayward Road as I sip my coffee.

I meet my team at 8:00 am. It includes my supervisor Shawn, our contractors, Curtis, Jake and Murray from Leighton Contracting, Teague from On Site Engineering, and Cedar, Matthew, Chrissy and Caelan, the K’omoks Guardian Watchmen. I put on my hardhat, steel toed boots and high visibility vest.

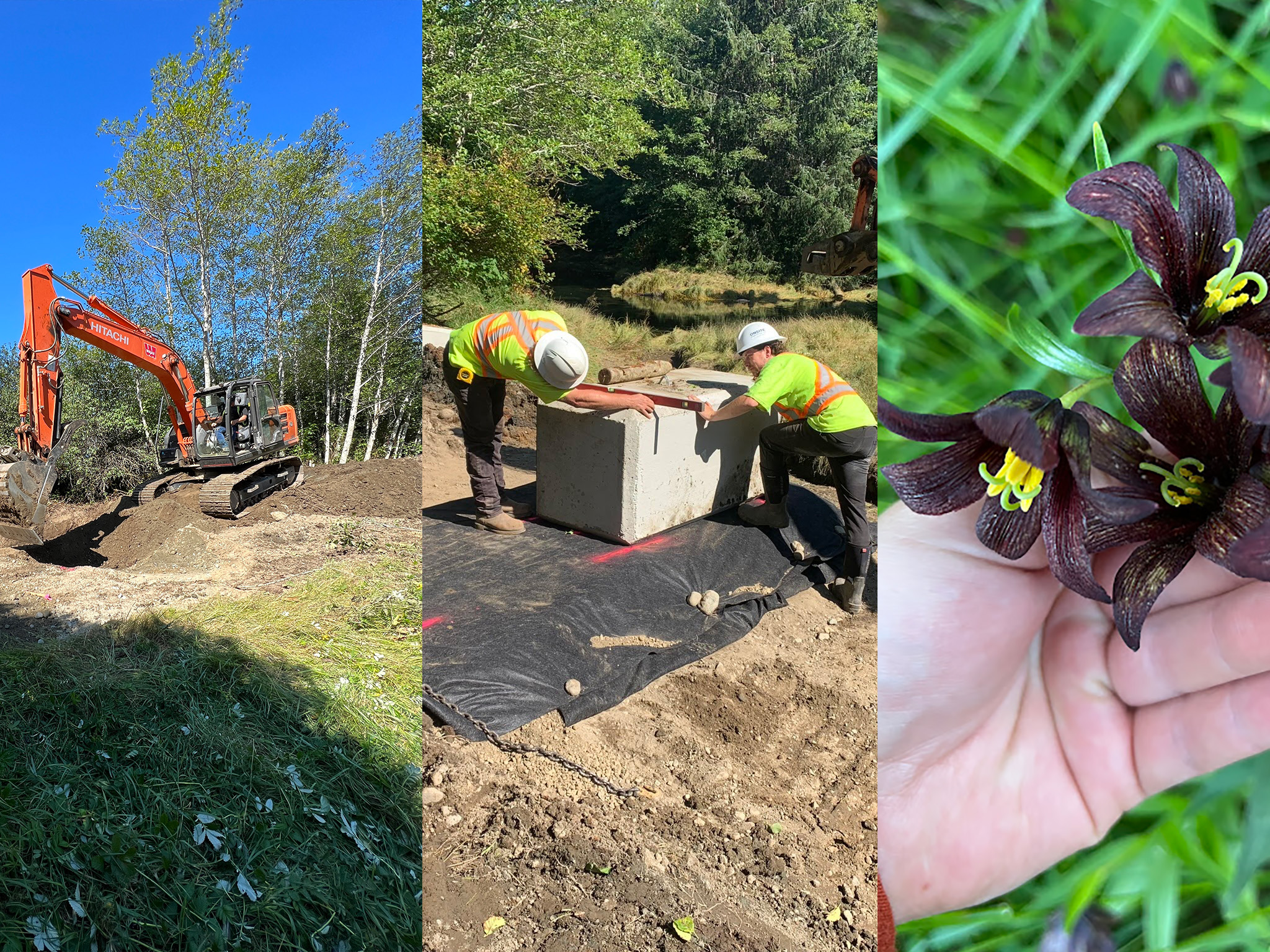

We stand around Shawn’s truck and finish our coffee as he briefs us on the hazards of the day as we will be working around Murray in his Hitachi 160 LC excavator. We sign the safety sheet and cross the street towards the trail head.

We walk together down the Salmon River Estuary Trail. A vestige of days where float planes landed in the estuary and lumber was sorted where the salmon swam. What is now the Salmon River Estuary Trail is a recreational walking trail moving through salmonberry and thimbleberry bushes with giant hemlocks and old-growth elderberries. This trail is a relic that once allowed for vehicles to drive in a loop, to and from the dock at the south end. The causeway unfortunately still cuts off the natural mixing of salt and freshwater on the Northeast side of the estuary and impedes the passage of countless species of fish, including Pacific salmon.

The Xwésam (Salmon) River Estuary is a beautifully complex system nestled in the Sayward Valley, framed by mountains where the Xwésam River meets the Johnson Strait, on the territory of the K’ómoks First Nation.

Our goal for this project is to breach the causeway, at two different points, removing material placed here to block the river from meeting the tides, and encourage that natural flow to support the function of the estuary while still allowing for the trail to be a site where visitors can appreciate this incredible ecosystem.

I’ve walked this path countless times over the summer. As a previous Conservation Field Crew member and now supervisor, I would normally revisit it once or twice a year for invasive species removal and trail maintenance. This season has been a different story. To prepare for the coming project, a great deal of work had to be done to ensure it was ready for the machine work to come.

A visit back in June with my crew of five included nesting bird surveys. This was done several times, not only completed by myself and my crew but also by Shawn, our Land Management & Major Projects Coordinator, and Curtis, our Senior Restoration & Monitoring Technician and RBTech. These surveys are an integral step in such a large restoration project. They allow us to ensure that no birds are nesting in the area when it comes time for heavy machinery to begin their work on site.

As we were scanning the canopy with our binoculars and combing the thick salmonberry bushes, an alarm call from a female Yellow Warbler let us know we might have found something. With a bit of searching, we spotted a baseball-sized cup, made from carefully selected mosses and fine twigs, balanced underneath a shelter of leaves. I carefully assessed the nest and found five small, speckled eggs. The nest was mapped, and the project could not proceed until the juveniles had fledged later this summer.

The presence of the warblers made our deadline to complete the project even more tight, as they aren’t the only wildlife who’s schedule we must work around.

While completing this kind of work in an estuary system, it’s imperative for us to plan around the cycle of the various species of fish who rely heavily on the use of its branching channels. This is especially important considering Pacific salmon. This timeframe is known as the ‘fish window’, the window to ensure that we will not be disturbing neither adults making their final swim upstream to reproduce, nor juveniles, starting their journey out of the streams and into the ocean.

The presence of the warbler nest has pushed the project right to the edge of our window. Now that we are finally on site, you can feel the looming deadline hanging in the air like fog. The pressure is on.

Our contractor and consultant’s role is to ensure public safety and the longevity of the bridges. The Guardian Watchmen are present as stewards of the territory, Shawn and I are here for the estuary. Fingers of low hanging clouds carried by a brisk wind roll over Mount Hkusam. Yellowing alder leaves float into the large pond sheltering sedge meadows. Fall has come to the Sayward Valley, while the South Island faces yet another late August heat wave.

We start our project farther down the trail, with Bridge Two. It spans a freshly excavated winding channel, the width of Murray’s smallest bucket and flooding only on a rising tide. We aim to preserve as much of its neighboring tidal meadow as possible, while still allowing for the flushing of saltwater as the tide comes in. This new channel now connects a tidal pond, flush with Lyngbye’s sedge and Coho fry, to a small channel on the east side of the causeway. It takes two excavators, countless measurements, and a lot of troubleshooting to place this first bridge and ensure it sits perfectly across our new channel.

I survey the fringing meadow. It had been studied earlier this summer, leading up to the project. At the right time in the season, it is filled with sedges and blooming wildflowers specific to meadows regularly inundated with saltwater. Rice-root, Henderson’s shooting star, yarrow, spring bank clover and silverweed are prolific in this special little pocket. Shawn and I discuss the planting plan to come this fall.

My official role on site is Environmental Monitor. I observe, record, report and offer advice when working within the new channels. At the beginning of each day, I check the tides and plan for the water quality assessment. I pack my bag and connect my monitoring device to my iPad.

I use the RBR Maestro datalogger to record the pH, conductivity, temperature, photosynthetically available radiation and dissolved oxygen of 7 different, predetermined collection points that will be influenced by these breaches. I do this so we can study the current specifics of water quality, and compare that to what it looks like during, and especially after the breaches.

Cedar and Matthew join me to help with recording data and positioning the device. We carefully make our way between the monitoring points, dawned in waders, walking through the forest, through different ponds and often tripping in small channels hidden by dense mats of sedge. Cedar tells me about historic fishing weirs and we watch juvenile Coho dart through the Lyngbye’s sedge while the data downloads.

Bridge One site is south of Bridge Two, closer to the road access, meaning it must go in last. Murray has placed the shiny prefabricated pedestrian bridge on log rounds at the south side of where the channel will be excavated. Once it has been dug, he will be able to roll the new bridge across. This bridge is set to replace a 2m culvert connecting two tidal ponds teeming with schools of Stickleback and Coho smolts, making it a more complicated site to work around, as the new channel will always hold water. We strategically plan our final week around the tides. Our goal is to avoid any fish coming too close to our worksite. Shawn, the Guardian Watchmen and I get back into our waders and drag a 50ft long weighted beach seine from the edge of the causeway, out into each pond and secure them on either side. This is to ensure no fish could be found in the work zone and exclude them from getting through during excavation. We gently guide starry flounders and schools of stickleback away from any potential harm. It is our contractors and consultants’ turn to watch us work.

This channel seems to be excavated much more quickly, and everyone takes a deep breath of relief as we become confident the project will be finished within the fish window. Purple Martins swoop and coast over the nearby river input channel and we hear Red-belted Kingfishers calling as Curtis and Teague guide Murray to set the footings for our last bridge installation.

It’s the moment of truth as the slings are set around the near end of the bridge and attached to Murray’s bucket. He slowly rolls the bridge along the alder rounds, and across the new channel.

We each took turns walking across the new bridges and taking photos of the incredible views of Mount Hkusam it provides.

The final ‘product’ looks very different from the path I walked so many times earlier this summer and last. What used to be dense salmon berry bushes and an impenetrable barrier to tidal fluctuations, now offers a widened trail with several beautiful lookouts that offer access for not only salmon, sculpins and the mingling of salt and fresh water, but also greater access for people to appreciate the Xwésam River Estuary.

I cannot wait to be part of planting these sites this fall and revisit them next spring.